Starting Seeds Indoors; part 1 of 2

By Pamela Page

Every year in March and April, I start an insane variety of herbs, fruits, flowers and vegetables from seed. To me, nothing is more miraculous, more mysterious or more gratifying.

They say you reap what you sow. I disagree. I plant small unpalatable things that cost almost nothing and weigh no more than grains of sand or small buttons. And yet, what I harvest tastes better and is more nutritious than almost anything I could buy and saves me more than $1,000 a year at the grocery store.

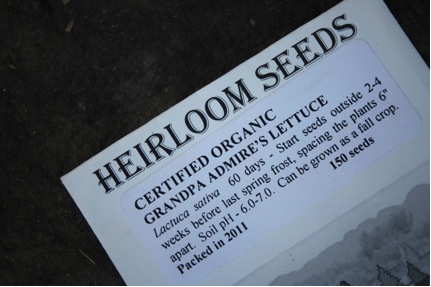

I buy mostly heirloom seeds – seeds from plants that have been passed down from generation to generation, and from plants whose seeds are not genetically modified or patented.

A vegetable’s life cycle is defined in terms of “days to maturity” which loosely translates into “how long does it take before this thing gives me something to eat?” And every vegetable is different. Therefore I sow the things that take the longest time to mature first – carrots, eggplants, peppers, tomatoes and marigolds, and the plants that require less time to mature such as melons, sunflowers, kale, basil and lettuce – after that.

Since you don’t want to set out your seedlings until weather conditions are right, if you live where it freezes, determine the last frost date for your zip code and then count backwards.

In Connecticut, our last killing frost is usually May 15th; therefore, I sow tomatoes, peppers and eggplant, eight weeks before then, around March 15th. Then I sow the seeds that require less time to germinate and mature a month before then – basil, beets, carrots, kale, lettuce, okra and sunflowers – around April 15th. I sow beets, carrots and lettuce every four or five weeks during the growing season.

I start most of my seedlings, or transplants, in covered plastic flats, not in a greenhouse, but in the three warmest places in my house – in my bedroom, bathroom and in the laundry room.

I plant in everything from toilet paper rolls and egg cartons to plastic cell flats under domes. Basil is easy to start in egg cartons. When is gets about two inches tall, you can transplant it to larger pots. You can start carrots in toilet paper rolls. It’s best to start tomatoes, peppers and eggplant in plastic flats with domes. You can find them at your local nursery or order them online.

Believe it or not, you don’t start seeds in garden soil. It’s too heavy and contains fungi and bacteria that could cause your seedlings to fail. You can buy sterile potting mix or, you can make your own organic growing medium.

Before I plant my large seeds, I soak them for a day or two in a weak warm solution of Vitamin C. Soaking gives the seed its first drink of water and nourishes the germ that will become a plant.

Planting big seeds is easy. Make a hole with a chopstick. Drop one seed in each cell. Read the seed packet for the recommended depth. Small seeds require fine motor skills. Tweezers make the task easier, but I don’t recommend this activity after more than one glass of wine.

Label your containers! There is nothing more frustrating than not knowing what’s growing. If you don’t feel like buying plant labels, coffee stirrers and wooden chopsticks will do just fine! Water the flat. Covering it with a dome keeps the soil moist, a must for successful germination.

The other critical thing is temperature. Seeds need heat to come to life. You could invest in a small heat mat. I keep my flats on the radiators in my house. On top of the refrigerator is another option.

Here’s a good chart for the required germination temperatures of each plant.

Not all seeds emerge or germinate at the same rate. Days to germination are listed on the chart and usually also on the seed packet.

Remove the plastic dome as soon as the seedlings emerge. Vegetables don’t thrive in a tropical rain forest and that is what keeping the domes on means.

The third thing they need is light – 12 to 16 hours a day. If you don’t have a really sunny spot, you will need a grow light. They come in all shapes and sizes.

The biggest challenge to keeping seedlings healthy is watering. Too much and your seedlings will rot. Too little and they will shrivel and die. Never pour water over the seeded area. Pour the water into the bottom of the container and allow the soil to soak it up.

Now as I write, a dozen flats surround me. Some of the seeds are still just seeds. I imagine they’re sleeping late. Others are nothing more than tiny pale white specks in a dark brown sea, while still others have begun to push their way through the potting mix, their tenuous stems curving like the necks of infinitesimal swans. I consider the strength the seed embryo must marshal to emerge from its hull and thrust through the soil so tomorrow he(?) or she(?) can stand straight with a silly round ball on his or her head – the first two leaves that will soon unfurl and look back at me.

A day later, I gaze at my ball-heads, and I bond. From this moment on, like any mother, no matter the joys or the heartache – and there will be plenty – a course is set. In the days, weeks and months to come, raising my brood to maturity – protecting, feeding, staking, pruning and ultimately harvesting – will be my first priority. But for now, I’ve got seedlings to raise and a few more seeds to sow.